WEEK NINE & TEN: TECHNOLOGY & TRADITION

My travels in New England during Thanksgiving week got me thinking about how digital technology can fit into traditional lifestyles. I spent part of my trip in a rural New Hampshire town called Alexandria, where my sister Monica recently moved with her husband Todd. They live right off the village green, which is about the most picture-perfect example of an old New England town center you can imagine.

My travels in New England during Thanksgiving week got me thinking about how digital technology can fit into traditional lifestyles. I spent part of my trip in a rural New Hampshire town called Alexandria, where my sister Monica recently moved with her husband Todd. They live right off the village green, which is about the most picture-perfect example of an old New England town center you can imagine. Except for paved roads, cars and telephone poles, the scene here is vintage Currier and Ives: virtually unchanged in the last one hundred and fifty years. Unlike other well-preserved places like Colonial Williamsburg or Old Sturbridge Village, however, Alexandria is not a museum or historic district, artificially frozen in time; it is just a place where people have seen little need for change.

Except for paved roads, cars and telephone poles, the scene here is vintage Currier and Ives: virtually unchanged in the last one hundred and fifty years. Unlike other well-preserved places like Colonial Williamsburg or Old Sturbridge Village, however, Alexandria is not a museum or historic district, artificially frozen in time; it is just a place where people have seen little need for change. Access to media must have been quite a challenge here until recently. The town library is open just three hours a week and has only a few hundred books. To compensate for this, satellite TV dishes have sprung up in many barnyards, alongside ubiquitous hand-pump wells and broken-down farm machinery. The village is also wired for cable television and broadband Internet. When my sister isn’t kayaking, cross-country skiing or making furniture in her barn, she works from home as a consultant in epidemiology. She does almost all of her work online on a laptop computer for clients ranging from a nearby clinic to a public health department in Washington State. Currently she is coordinating an interdisciplinary project to help farmers in Washington avoid disease resistance in cows by curbing overuse of antibiotics in the animals' food.

Access to media must have been quite a challenge here until recently. The town library is open just three hours a week and has only a few hundred books. To compensate for this, satellite TV dishes have sprung up in many barnyards, alongside ubiquitous hand-pump wells and broken-down farm machinery. The village is also wired for cable television and broadband Internet. When my sister isn’t kayaking, cross-country skiing or making furniture in her barn, she works from home as a consultant in epidemiology. She does almost all of her work online on a laptop computer for clients ranging from a nearby clinic to a public health department in Washington State. Currently she is coordinating an interdisciplinary project to help farmers in Washington avoid disease resistance in cows by curbing overuse of antibiotics in the animals' food.Monica is certainly not the only wired professional in the village. One day she took me to the town selectman’s office, located in one of the newer buildings (built in 1903) on the village green. In a tiny office on the second floor, across the hall from the town’s one-man police department, the town clerk sat beside a propane stove working on an Excel spreadsheet. As she helped Monica research some land for sale, the clerk spoke with deep disdain of a nearby county office that does not have its records online.

Another day, Monica took me to visit a nearby Shaker museum. I always assumed that Shakers were severe traditionalists like the Amish or the Mennonites, but the tour guide here set me straight. Although Shakers believe in a simple life and are traditionalists in some areas such as dress, they have always been quick to embrace new technologies that can make work easier and increase the quality of their famous products, such as furniture and wooden storage boxes. Shakers believe that striving for perfection in their work is a religious duty and also that the less time work takes, the more time they can devote to religious meditation. The guide told us about several labor saving devices invented by Shakers in the 19th century, including a circular saw and one of the earliest patented mechanical washing machines. He told us that the few remaining Shakers, who all live in a village in Maine, today make use of computers, cell phones and other modern devices they see as enhancements to their traditional lifestyle.

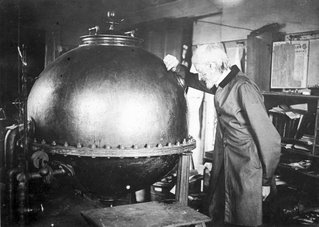

Another day, Monica took me to visit a nearby Shaker museum. I always assumed that Shakers were severe traditionalists like the Amish or the Mennonites, but the tour guide here set me straight. Although Shakers believe in a simple life and are traditionalists in some areas such as dress, they have always been quick to embrace new technologies that can make work easier and increase the quality of their famous products, such as furniture and wooden storage boxes. Shakers believe that striving for perfection in their work is a religious duty and also that the less time work takes, the more time they can devote to religious meditation. The guide told us about several labor saving devices invented by Shakers in the 19th century, including a circular saw and one of the earliest patented mechanical washing machines. He told us that the few remaining Shakers, who all live in a village in Maine, today make use of computers, cell phones and other modern devices they see as enhancements to their traditional lifestyle. Shaker inventor with a vacuum pan evaporator for distilling medicinal herbs

Shaker inventor with a vacuum pan evaporator for distilling medicinal herbsLater that evening Monica told me about a different community where traditional ways and new technologies meet in stark contrast. She and Todd were traveling recently in the Himalayan region of India, were they observed many homes where heating and cooking were done with indoor fires. None of these homes had fireplaces or chimneys, however. Smoke simply filled the living quarters until it seeped out through cracks in the ceilings. A few buildings, such as a café where they stopped for refreshments, had woodstoves equipped with chimneys, but their owners apparently had no idea how to use them. People shoved long logs into them, leaving the stove doors open so that, without proper draft, smoke poured out and filled the rooms, just as in the homes without stoves. Monica remembers coughing and rubbing her eyes constantly, as did the other inhabitants of the café. Ironically, this place was a sort of INTERNET CAFÉ where people were working on laptops and talking on cellphones! People in this remote mountain region had no problem adopting technology only a few years old but had yet to come to terms with other technologies that have been around for centuries.

Finally, at our family reunion in Manchester New Hampshire on Thanksgiving, I talked to an elderly relative who simply refuses to accept Internet technology. She complained that her children had forced her to get a computer so they could communicate with her by email. Now, she said, she is getting ten, fifteen emails a week from all sorts of people, and she doesn’t know how to cope with them. I tried to give her advice, but she lampooned everything I said until I finally advised her to take her computer out to the dumpster, throw it in and be done with it. This was the only answer that pleased her. I picture her now, writing a letter or two as she sits by her fireplace – presumably one with an excellent chimney. High tech may be fine for New Hampshire farmers, Shakers and Himalayan villagers, but it’s not for everyone.

………………………..

One of this week’s weblog assignments was to write about a new technology we have adopted. The most recent technology I have adopted is digital still photography. I had a nice film camera many years ago, but gave it up when I started shooting video. I found shooting stills on film to be nerve wracking because I always seemed to press the trigger about three seconds too late, and never knew what I had really shot until I got the film back from the lab. Often I would be disappointed because my exposure would be off. Video was exciting when it became affordable in the 1980s because I could capture action continuously, and although the early viewfinders were black and white, I could pretty much see what I was getting and whether or not it was exposed properly.

Using Rogers five stages of adoption, my history with digital photography runs as follows:

1. KNOWLEDGE: I began to see a lot of people using digital cameras. When I got a computer-based video editing program, I realized that I could use my video cameras to shoot still images and then edit and print them through my computer. It was thrilling to be able to create still images this way and incorporate them within documents and emails.

2. PERSUASION: I realized that digital cameras have a lot of the same features that I like about video cameras, including auto exposure, a viewfinder that shows you pretty much what the final image will look like (WYSIWYG) and the ability to shoot lots of images without incurring large costs. What I did not like about the early digital cameras was the several-second delay after pressing the trigger. When I heard that this problem had mostly been solved, it weakened my resistance to trying this new technology.

3. DECISION: When I blew up stills from my video cameras, I realized that I was getting much lower resolution than I could achieve with even a cheap digital still camera. So I took part of my pay from a video production job and bought a pretty nice Canon point-and-shoot.

4. IMPLEMENTATION: I tried this camera out on a trip to Las Vegas with my best friend Jennifer, who, sadly, had recently been diagnosed with terminal cancer. Shooting pictures of her at night on the Strip, I quickly realized that I preferred shooting with available light, instead of shooting with a flash. When I got back from the trip I was disappointed that many of my night images were blurry. Then a friend told me about still cameras that have digital image stabilization – just like my video cameras – to correct for hand movement during the long exposures needed in low light. So I upgraded to a Canon with this feature.

5. CONFIRMATION: Although the new Canon had lower resolution than the first one, my low light pictures turned out better. One of my favorite resulting pictures was this image of Jennifer, taken under very low light during a Christmas party at the restaurant where I work. I added paint filters in Photoshop and used it for Christmas cards last year.

Later I realized that I could also shoot short video clips with my new still camera. I began using it to shoot video on many occasions when it was not practical to bring along a larger video camera. When Jennifer’s father came to visit, shortly before she died, I was able to capture their last moments together in video thanks to my digital still camera. This footage became an important part of an hour-long documentary I made for Jennifer’s family about the last two years of her life.

Later I realized that I could also shoot short video clips with my new still camera. I began using it to shoot video on many occasions when it was not practical to bring along a larger video camera. When Jennifer’s father came to visit, shortly before she died, I was able to capture their last moments together in video thanks to my digital still camera. This footage became an important part of an hour-long documentary I made for Jennifer’s family about the last two years of her life.I love the fact that I can now shoot pictures casually, just for the heck of it, instead of being filled with anxiety as I was whenever I shot stills in the old days. Now I am even thinking about getting a digital SLR so that I can get better manual focus control.

………………………..

Our other blogging assignment was to write about how we used digital technology to cope with the recent snowstorm in Seattle. I first learned about the “storm” when I looked out the window of the airplane that brought me back from New England and saw snow on the ground. Knowing that Seattle has virtually no ability to cope with snow, and that what constitutes a nice winter day in New England can be considered a “state of emergency” here, I simply put on my warm cap, started humming Christmas carols and knew not to expect to get anywhere very fast. The only time I used digital technology during the “storm” was when I took out my digital camera to snap a picture of my cat sniffing some dried weeds I brought from New Hampshire and stuck into the snow on my lawn.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home